Every fire department’s got one of them, or if they don’t, they know one of them: the person who knows every little model number and fact about every light fixture on the market. They can state how many flashes per second, how many lumens, and what the year a specific fixture was released. But, as valuable as all that data is, can this person also articulate where the optimal placement of each fixture is so that firefighters aren’t blinded when they are on scene at their next emergency?

A variety of FAMA member companies manufacture technologies designed to help firefighters work more effectively after dark. Often, firefighters and lighting manufacturers alike get side tracked with things like making sure they consider the number of LEDS, and the number of lumens. In addition, they must keep in mind, the placement of other firefighting appliances on their apparatus so that existing scene lights do not get obstructed. With all of these things to keep in mind, the fundamentals of a complete and rock-solid scene lighting package can get overlooked.

By keeping the following four fundamental principles in mind, your apparatus specifying committee can build a truck that not only looks sweet, but also gives you an edge when you are out at night saving lives and protecting property.

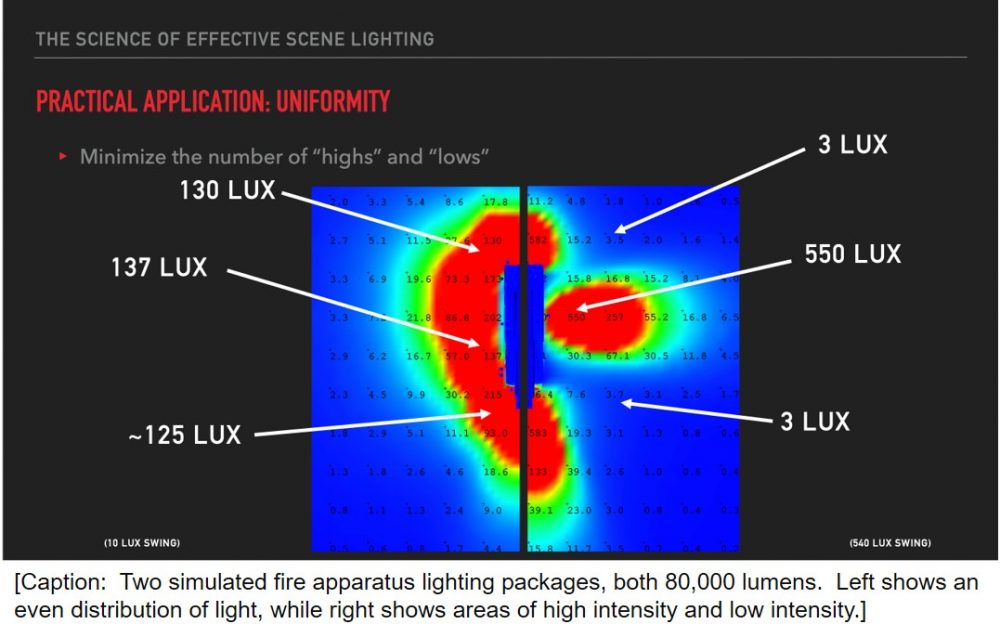

The name of the game in working after dark is uniformity. The intensity is less important; the number of times the firefighter’s eyes have to transition from very bright light to very dim light is what causes strain on the operator. It is more important to have an even intensity of lighting around the vehicle and fire scene than it is to have one spot in particular extremely well lit. Consider installing a greater number of fixtures with a lower intensity each, around the apparatus to create an evenly illuminated work space. Many FAMA member companies can even draw your apparatus digitally before manufacturing to help you visualize how the beam patterns will perform.

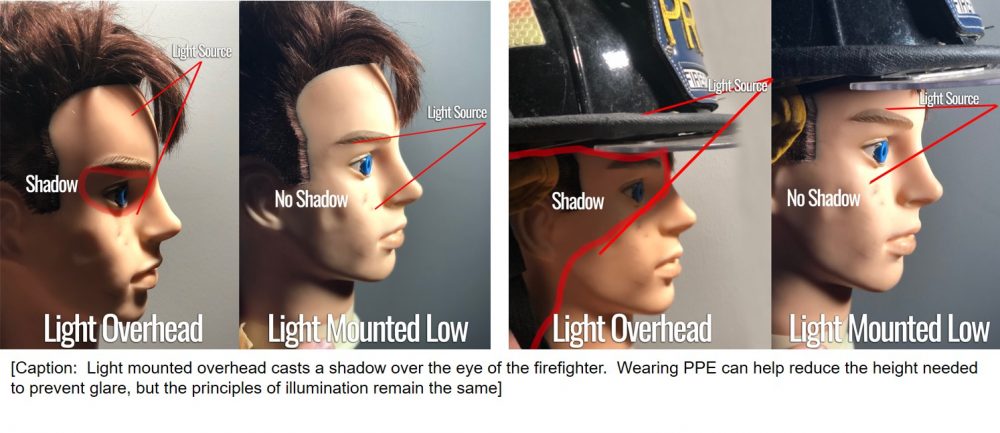

Humans have evolved to work with the sun shining down from overhead. As such, leveraging the evolutionary science and biology of our species during spec writing is helpful in reducing glare on fire scenes.

Here’s the science: humans have two eyeballs each recessed in to a socket on the frontal bone of the scull. Above that socket, there is a bony structure called the supraorbital ridge over which the eyebrows typically align. When the sun shines down on a human’s skull, this bony structure, coupled with the eyebrows and eyelashes, casts a shadow which typically occludes the eye and prevents the sun from shining directly in the eyes of people as they work. When specifying a fire apparatus, firefighters should keep the basic biology of the human body in mind, and specify scene lights which can be placed as high overhead as practical, so that the Firefighter’s PPE and the natural shape of the human skull help prevent glare from hitting the crews in the eyes at night.

Lights can be placed high up on the body, on poles, or even on light towers to help reduce glare.

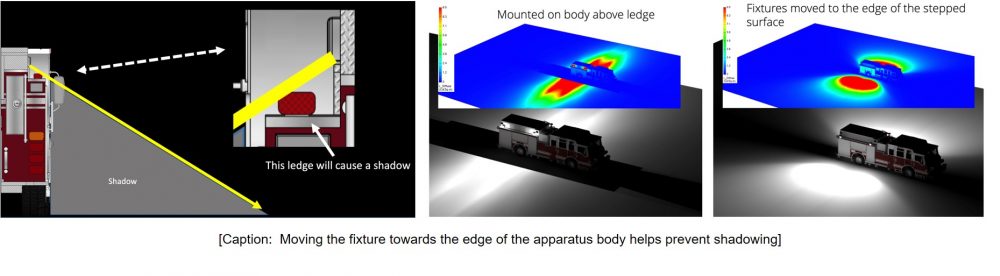

Light doesn’t bend! Think about fixture placement and the shadows that will be created when you select a mounting location! If you mount a scene light with asymmetric optics on the side of a stepped pumper body (say, on the vertical surface near where the hard suction may be attached), if the beam shines “down” and “out” from the fixture and a horizontal portion of the body is below it, a shadow will be cast along the edge of the body on the ground. In these situations, consider bringing the fixture out towards the edge of the apparatus to prevent these shadows from occurring. Light can not bend around the profile of the truck, if its obstructed, you will have a shadow.

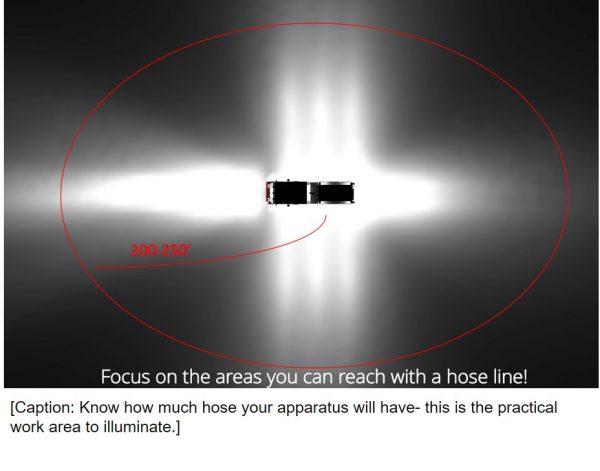

You’ve only got so much hose! The vast majority of the time, when operating off the fire apparatus at night, you will be tethered to the apparatus by a piece of hose. When writing a specification for scene lighting on a fire apparatus, consider the length of hose and the most frequent operating characteristics of the apparatus for scene lighting design. If the truck has 250’ of cross lay, there is no need for scene lights than can shine 1,000 feet down the road. Focus on the areas you can reasonably expect to work in and supplement your scene lighting package with portable or battery/generator/extension cord powered fixtures for the “what if” situations.

Conclusion: Many FAMA member companies build products specifically designed for the Fire Apparatus industry. When designing an apparatus, reach out to the manufacturers of the equipment you are considering, and invite them in to help guide your committee on fixture placement. For more general information about scene lighting, as well as a variety of other topics related to fire apparatus equipment, check out the FAMA Buyers guides online at https://www.fama.org/fire-service-resources-list/